|

|

|

The Films of David Lynch Authorship and the Films of David Lynch Introduction Chapter 1: Eraserhead Chapter 2: Elephant Man/Dune Chapter 3: Blue Velvet Chapter 4: Wild At Heart Conclusion Matt Pearson 1997 50 Percent Sound Introduction Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Conclusion Philip Halsall 2002 Bibliography Resources |

|

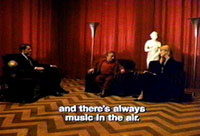

Chapter 4: Wild At Heart The Commerce of AuthorshipAmongst the many forms of discourse that bombard us daily, there are very few that we require authors to be assigned to. It is unimportant to us to question the authorship of documentaries, advertisements, music videos or soap opera plot-lines. It is only since the renaissance that artistic discourse became the work of the individual artist, and only since 1948 that film acquired an auteur. Nevertheless, following the critical success of Blue Velvet, Lynch's name became hot property and, between 1989 and 1991, was branded onto adverts ('Obsession' for Calvin Klein, 'Opium' for Yves Saint-Laurent, 'Refuse Collection' for New York City), pop videos (Chris Isaak's 'Wicked Game', Michael Jackson's 'Dangerous'), a painting exhibition of his early work, an album ('Floating into the Night'), a live show ('Industrial Symphony No.1'), a series of documentaries ('American Chronicles' which Lynch produced), a situation comedy ('On The Air') and, of course, a television soap opera (Twin Peaks). Wild At Heart was the film that accompanied this surge of output. It was a road-movie inversion of Bonnie and Clyde(Penn 1967), with two lovers the only 'normal' people travelling through a world that is "wild at heart and weird on top". It contains many parallels in theme to what had happened to its director, the fact that he had become a marketable property, a commodity. Timothy Corrigan, in 'A Cinema Without Walls', proposes the "commerce of auteurism", with the director becoming a selling point as much as the stars of a film. Post-60's, he says, auteurism became a method "to locate the expressive core of the film art". The director carried "a recognition either foisted upon them or chosen by them", i.e. directors developed star personas of their own. Godard said "in today's commerce we want to know what our authors look like, how they act ... it is the text that may now be dead." Michel Chion describes Lynch's star persona: "The considerable world-wide success of The Elephant Man made Lynch into a popular figure. Interviewers were struck by his rosy-cheeked, well-behaved exterior and his studied dress sense ... Stories made the rounds about his pastimes and his innocent eccentricities: building cabins and dissecting animals, collecting dead flies tacked on panels, amassing piles of rubbish, and so on. Mel Brook's description of him as 'a James Stewart from Mars' was widely repeated."When this star persona becomes a marketable quality, it is a producer's interest to promote the presence of an auteur within their production set up, even if they are only present in the capacity of Executive Producer (The 1995 film Crumb was promoted with the line "David Lynch presents ..."). Safe bet directors became the replacement for faith in the studio system. According to Sarris, the auteur theory leads us to believe that a bad John Ford is better than a good Henry King (to use his example). Auteur analysis means that there is something worthwhile to be found in the worst of an auteur's films, therefore it is impossible for him to make a truly bad film. This, of course, is the principle selling point of the commerce of authorship, the auteur once established becomes a 'seal of quality' on a work. Corrigan says: "The international imperatives of post-modern culture have made it clear that commerce is now much more than just a contending discourse: if, in conjunction with the so-called international art cinema of the sixties and seventies, the auteur had been absorbed as a phantom presence within the text, he or she has rematerialised in the eighties and nineties as a commercial performance of the business of being an auteur." Once auteurism becomes a marketable quality it makes us suspicious that, if there's profit to be made, maybe the auteur status is fakeable. Director Francis Ford Coppola is a proud spokesman of the idea that an auteur earns his status through commercial success. This is a very 'Eighties' idea, in line with the Reagan/Thatcher ideology that the market could be used as a judge of value, even artistic merit. Many directors known for their experimental style developed (or 'evolved into' maybe) a more bankable style especially during the Eighties, for example Martin Scorsese's After Hours(1985) and The Color of Money(1986). The Elephant Man and Dune seem to fit this picture, being much more commercial films than the preceding Eraserhead. But, according to Coppola, should the failure of Dune at the box office rob Lynch of his status? We know, with the benefit of retrospection, that Blue Velvet was to restore Lynch's artistic reputation. In Lynch's case he doesn't seem as compatible with the commerce of Hollywood as Coppola, in some way the critical backlash that Wild At Heart prompted, it's rejection by the establishment, is reassuring. The value of the director as selling point of a film was a concept familiar to art cinema but was new to commercial cinema. This is an example of the post-modern drift across boundaries of 'high' and 'low' art. Another aspect of post-modernism I omitted from the last Chapter is the objectification of people and concepts, the commodification of everyday life. With the post-structuralist auteur theory the auteur is no longer a 'real' person but a construct within the text, i.e. they have become objectified. This is referred to thematically in Wild At Heart, Sailor's jacket is a "symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom"; his ideology has been reduced to a single object. Similarly Lula is objectified, Sailor turning her body in bed cuts to him turning a novelty erotic pen. In Twin Peaks, in Laura's absence, her photograph becomes a character. In Blue Velvet, Dorothy's child is represented by his toy hat and Sandy's concept of love is reducible to a synthetic mechanical bird. The road movie is an apt genre to approach commodification; the car becomes a symbolisation of its owner, in this case it becomes a shared identity of Sailor and Lula. When Sailor is lured into the Heist he goes in Bobby Peru's car, thus absolving the car shared by Sailor and Lula from evil. Sailor even sings his marriage proposal from the roof of their shared car. Not only does Wild At Heart express a self-referentiality to the auteur structure behind the work through its commodification theme, the multitude of references to that other 'road' movie, The Wizard of Oz, relate directly to Lynch's awareness of his own authorship. Marietta is cast as the Wicked Witch of the West, the Good Witch appears in the final sequence. Lula clicks her heels together longing to escape the world she is in while the script makes references to the yellow brick road and Toto the dog. Michel Chion says "The Wizard of Oz seems to symbolise for Lynch, or at any rate in the use he makes of it, two important, related themes: multiple worlds (Oz and Kansas) and the divided mother (the two witches)". By referring to this film he is acknowledging the presence of his own thematic preoccupations. As with Blue Velvet there is a great deal of intertextual referencing to other films of the road-movie genre, placing it in its cinematic tradition. John Orr, in "Cinema and Modernity", says Wild At Heart "borrows heavily from Weekend and remakes Badlands, Touch of Evil and They Live By Night". But the convention is subverted; as Kit was James Dean in Badlands(Mallick 79), Sailor is Elvis, the fuel as metaphor for restless energy becomes potentially explosive with the presence of matches and cigarettes Wild At Heart won the Palme D'Or at the Cannes film festival in 1990, an unpopular decision. Chion says "some people took the opportunity to voice their distaste for a film-maker who had always seemed dubious to them and whose present film appeared to confirm an aesthetics of phoniness and fakery". This 'phoniness and fakery' was Lynch's post-modern representation, the conscious reference to the mode of production, as discussed in the last chapter. With Wild At Heart, Lynch had done for the road movie what he had done for the film noir with Blue Velvet, blurring generic chronotypes in a post-modern spectacle. For this he was accused of being formulaic, sticking to Blue Velvet's winning formula and being 'weird for weird's sake' (a criticism often levelled at Twin Peaks). It would seem that after only five films the critics were bored with the Lynchian perspective and demanded something new. Corrigan cautions, "the celebrity of [the auteur's] agency produces and promotes texts that invariably exceed the movie itself." But can we criticise Lynch for being formulaic, is this not what the auteur theory is all about, a consistency across a set of films. Do we demand that he innovates with each film, or is it anti-auteur to go against expectation? This relates back to the idea of the auteur 'evolving' as discussed in Chapter 1. One consequence of the commerce of authorship is that authors are made and dismissed a lot more quickly. A critic such as Sarris certainly wouldn't accept Lynch on a par with Ford or Hitchcock, but marketing men of the 90's would be keen to ascribe such worth to a director as early into their career as possible (see the example of Quentin Tarantino who became an auteur after only one film). Truffaut said "whereas he and his colleagues had 'discovered' auteurs, his successors have invented them" (quoted by Sarris), Now, as Corrigan says, "auteurist movies are often made before they get made", they create a critical expectation that makes viewing the actual film unnecessary. This way of judging an auteur seems a far cry from the 1948 Cahiers du Cinema concept. Is it possible that the current definition of 'auteur' is too open, it is a club unpopular by its lack of exclusivity. |